Last week, a colleague told me she’s from the same hometown as Zhou Enlai (周恩来 the first Premier of the People’s Republic of China): Huai’an (淮安) in Jiangsu province (江苏省). I had never heard of that place, and it’s the same thing when people tell me they’re from Kaifeng (开封) or Weifang (潍坊) — or when I’m looking at the high-speed train map of China. I know Shanghai and Nanjing, but not the six stations in between. I look these cities up on Wikipedia and discover that millions of people live in each of these, I feel ignorant, but also intrigued. Each day life is lived there; photographs are taken, dinners are eaten, and children are born.

The unknown side of China

When you search for lower-tier cities on Google or Baidu, you get nothing but grey skies above a wide river, a park with leafless trees, and maybe an aerial photo of a new harbour project or monotone residential area.

I look these cities up on Wikipedia and discover that millions of people live in each of these, I feel ignorant, but also intrigued.

These cities are often described as “dingy”. The main attraction on TripAdvisor is a local park or pagoda, and sometimes there’s a blog from an English teacher that sums it up as: “I taught a year of English in this city, wouldn’t recommend it.”

Trying to break preconceived notions

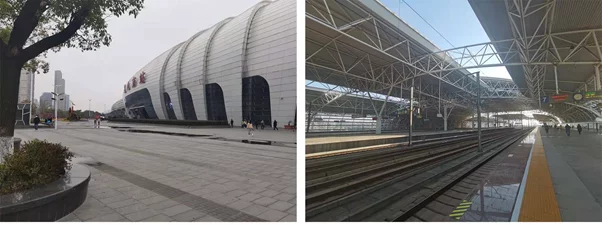

I picked Danyang (丹阳) in the Jiangsu province. It’s under the administration of Zhenjiang (镇江). China has 388 county-level cities like Danyang, and 293 prefectural-level cities like Zhenjiang.

I left the new train station, turned a corner, and stopped dead in my tracks: I’m looking at those same grey photos from Google and Baidu now. I see a canal occupied by a caravan of cargo ships. The whole scene is rather… grey, dingy, and just like those Google images I saw.

Is it going to be hard to get a fresh impression of lower-tier cities?

Each city block seems built in a different decade (and different philosophy) — with odd buildings here-and-there.

But there is life in Danyang, alright. The park is one of the top attractions and it’s well-maintained. There’s a pagoda which seems to have been built only a few years ago, and exercising seniors, young parents with their kids, and middle-aged guys photographing fauna with SLR-cameras.

Each city block seems built in a different decade (and different philosophy) — with odd buildings here-and-there. A green-yellow-blue police station, a Greek temple, a yurt. More into the city center I find a wet market, and people are surprisingly friendly. But at the end of the day, I’m still not sure how to feel.

Far into the Zhejiang province

I try my luck at Jiangshan (江山) in the Zhejiang (浙江). Online, I can only find a few images of it, and everyone I tell about my travel plans has never heard about it (Chinese friends included). Its population of 613,000 people falls under the jurisdiction of Quzhou (衢州), 40 kilometres east.

The taxi driver took us to the city’s name-giver, a mountain called Jianglang (江郎山), and on the way there he spoke about his youth, how back then these highways weren’t there, and how people were just happy if they could eat and send their kids to school. How different now, he added.

There seems not much to do, but these cities are well-developed, thanks to their factories and close connection to Shanghai.

The city itself is trapped between the river and the mountains. And I like the whole vibe. Almost nothing towers above five floors. There’s one KFC, one Starbucks, and one Pizzahut. People gather at night to dance or sing. Some elders who know a few words of English want to make small talk, while mothers push their kids to use English with me, and record and share it on WeChat.

Satellite cities

The cities Kunshan (昆山) and Taicang (太仓)’s biggest benefit is often described as; “well, it’s close to Shanghai”, or “yeah, there is a Starbucks.” There seems not much to do, but these cities are well-developed, thanks to their factories and close connection to Shanghai.

In Kunshan, we were drinking coffee in an independent shop, when another customer tells us it has only been a decade since Starbucks first opened here, and now the block has almost forty coffee stores. He is a baker himself, and shows photos of his French baguettes and tells me how to make the perfect crust. And to me, that’s the miracle. Another Nike store in Shanghai does not impress me, but a guy in a lower-tier city talking about how to make the perfect baguette does.

Taicang is up next, and it would have looked more flattering in the sunshine, but winter clouds are what we have, and everything looks sombre because of it. Even most cars are colourless. Yet facilities look great; Sharing bicycles and huge new avenues.

The new museum and library (built next to each other) are a typical sign of development in China, with modern architecture that wouldn’t look out of shape in Shanghai. The museum shows the city’s rich history in the Yuan and Ming Dynasty, recreated with scenes and boats. Some porcelain shards are the only tangible evidence left, the rest destroyed in rebellions or bulldozed for shopping malls and factories.

The new museum and library are typical signs of development in China, with modern architecture that wouldn’t look out of shape in Shanghai.

Taicang is Shanghai’s playground for the weekend. Aside from huge residential blocks, there’s a huge mansion park surrounded by golf courses, and all the license plates are from Shanghai. There’s a fairytale park with hotels, yet like all Evergrande projects brought to a standstill.

Making sense of lower-tier cities

Every lower-tier city has its own flavor. Danyang is China’s spectacle city. There are three shopping malls filled solely with stores for spectacles that you can bulk-buy.

Jiangshan mostly has factories that make either fire extinguishers or doors — and the product in-between: fire-resistant doors.

Kunshan is home to many Taiwanese businesspeople and factory owners, while Taicang has lots of German factories, over 400 of them, even if the German businesspeople themselves prefer to live in Shanghai.

Every lower-tier city has its own flavor.

It’s easy to be cynical about lower-tier cities: Swanless ponds and colourless avenues, parks where trees grow in neatly aligned grids, and the same for residential areas. Museums are filled with fake stuff because the originals have been destroyed or lost.

But, the cities are modernising rapidly, such as Kunshan, which is “near a tier 1 city”. Modernising means new cultural facilities (museums, libraries, or theatres), sports facilities (pools, outdoor sports parks with basketball and football fields), and transport (high-speed-train connection, fantastic highways, and Electric Vehicle charging stations) are made available in the city. Moreover, Kunshan is even getting a subway.

Walking around the cities you can see the change. I’m assuming you read this from a tier-1 city in China, or from a Western country, and this all may not seem much to you — but for a huge part of China, it will.

Read more: