It might not be done intentionally, but national pride has long been weaved into the Olympic Games, and no country has taken that pride more seriously than China. The pride, however, didn’t come until 2001 when Beijing was awarded the ability to host the 2008 Olympics, which was described as “a symbol of rejuvenation” for the country, to wipe out the stereotyped memory about Chinese acrimony.

To do so, China sent the then biggest-ever Olympic team of 639 athletes to compete on home soil and lavished a record $43 billion on hosting the international sports event, including the extravagant opening ceremony that showcased its historical glory and new achievements. Pressures were not only on organisers but also athletes, who were expected to pull off sporting success in order to produce a monument of national pride.

The efforts paid off. The host topped the gold medal tally for the first time in 2008, amassing 48, beating the United States who had a second-largest haul of 36. Although the country experienced a let-down at the following London Olympics, slipping to the second with 38 golds, and an even bigger disappointment was seen at Rio in 2016 when China fell to the third with 26 golds after the US (46) and the UK (27). The decline in Olympic performance has only aroused China to double down its efforts in building up its soft power through sports, further spurring the country and using this disappointment as a catalyst for future dominance.

Pressures were not only on organisers but also athletes, who were expected to pull off sporting success in order to produce a monument of national pride.

The government had promised to build a sports industry worth $813 billion by 2025 and vowed to build a strong sporting nation by 2050. With these ambitions, Tokyo 2020 came as the latest stage to showcase its strength and bring back its national prestige by “remaining on top in terms of gold on the medal table”, as said by Gou Zhongwen, former director of China’s Olympic performance.

The message was sent one week ahead of the Games when China unveiled, once again, its largest-ever overseas Olympic delegation, consisting of 431 Chinese athletes. Although China failed to reclaim its first place on the medal table, the outcome was still applaudable and showed motivation across the nation. With 38 golds, China was in second place, slightly behind its American counterpart who topped the rank with 39 golds. This time, China seems to be less disappointed, due partly to the declined obsession for gold medals at home. With China building up towards a global sporting power, the number of medals seems to be less relevant, which on first glance sounds confusing.

On the other hand, with the nation’s pride in sports growing, athletes at these international events are viewed as national heroes and celebrated regardless of their results. This national sentiment has soon turned athletes into China’s new national “idols”, and therefore, become sought-after by brands who want to leverage their popularity among Chinese consumers.

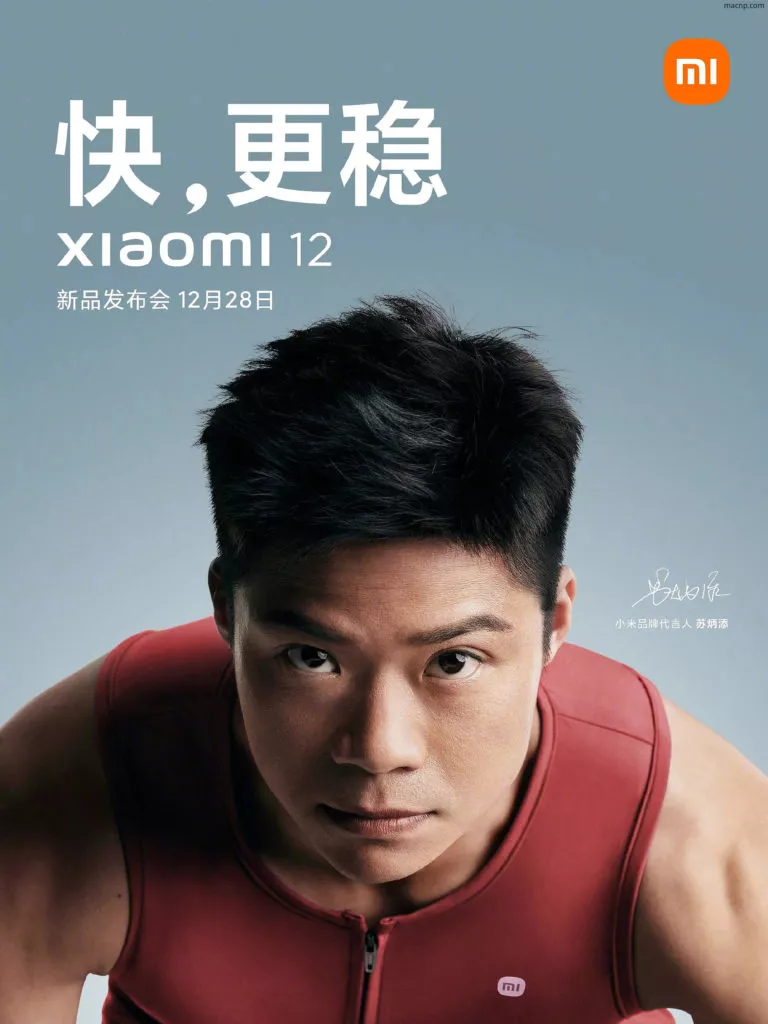

Take Su Bingtian, China’s sprint star, who made history by being the first Chinese runner to qualify for the men’s 100 metres final at Tokyo 2020. Despite finishing sixth in the final and missing out on a medal, Su won the name of “a gold medallist without a gold” at home and has so far been signed to be a brand ambassador for nine brands, including Xiaomi, a Chinese smartphone maker.

With the nation’s pride in sports growing, athletes at these international events are viewed as national heroes and celebrated regardless of their results.

Not until after the 2016 Rio Olympics did Olympians start to catch brands’ attention, and only a handful of athletes gained more public exposure through TV shows, thanks to their broadcasting personality. However, this has not been the case anymore after Tokyo 2020, with a recent surge in their star status, brought about by a few factors.

“There has been a growing number of brands turning to athletes for collaborations since the Tokyo Olympics,” said Zhu Xiaodong, CEO of Sponsor Force, an online platform connecting brands with professional sports for sponsorship. This is due partly to the tighter scrutiny from the Chinese authority on the entertainment industry, which sees a series of celebrities fall from grace, further, putting brands’ reputations at risk. With multiple celebrities causing media scandals and a few facing jail time due to their actions, it has left a lot of brands reluctant to engage them, leaving a gap that has started to fill with virtual influencers and now Olympic athletes.

In addition, the ongoing guochao trend has been fuelling the national pride in sports among young Chinese, who are the main followers of this national wave. This has driven changes in the audience base of these international sports events in China. In response to the change, marketers are also swift to shake hands with those sports celebrities in order to win over this lucrative demographics of consumers.

There has been a growing number of brands turning to athletes for collaborations since the Tokyo Olympics.

As a result, a total of 13 Olympic gold medallists from Tokyo 2020 have made their debut in commercials, representing a total of 32 brands which is a stark contrast to the fortunes of Olympians prior to Tokyo 2020. Namely, Yang Qian, the Chinese sports shooter who picked the first Olympic gold medal at Tokyo 2020, sparked another wave online after she shot the fame, by making her appearance in Estée Lauder’s advert for the brand’s 7th Generation of Small Brown Bottle. Each of the two posts made by Yang on her own Weibo account was engaged by more than 100,000 people, highlighting just how much brand power and influence these sports stars can have.

Also being pursued is Sun Yiwen, who cliched women’s épée individual gold at Tokyo 2020. The épée fencer has so far partnered with four brands, including American skincare brand Olay and Italian sportswear brand Kappa.

With the building of a sporting nation continuing to be one of the top priorities of the Chinese government, the country’s enthusiasm for sports is expected to grow.

Even Quan Hongchan, the youngest Olympian who competed at Tokyo 2020, is reported to potentially become a brand ambassador for Xtep, a Chinese sports apparel brand, who had already secured another athlete Gong Lijiao, a Chinese Olympic shot putter. The then 14-year-old Quan became a national sensation after claiming gold with three perfect-10 dives, with the hype towards this teen diving star expected to boost Xtep’s appeal to its teen consumers.

With the building of a sporting nation continuing to be one of the top priorities of the Chinese government, the country’s enthusiasm for sports is expected to grow. So would the popularity of China’s athletes. While this has provided another safer option for brands for celebrity endorsement, it remains to be seen if this could turn into commonplace for brands’ collaborations, considering athletes’ uniqueness of their profession in sports.

More importantly, in seeking partnership with those athletic stars who are part of the national team, it means they would have a closer relationship with the government. This has the potential for brands to take extra efforts to secure one of those Olympians due to the potential dealing with the authority, who might not want the spirits of sports that are carried by athletes to be commercialised.

Read more: