For a long time, burning incense and worshipping in front of Buddha, was regarded as a superstitious activity that was only practiced by elders in China. But now the younger generations are adopting the ritual in China’s ancient temples. Instead of praying for a sweet relationship, securing a job and future prosperity in their careers have become priorities amongst these young devout worshippers.

Tourism attractions born from temples and monasteries across the nation saw a more than three-fold increase in bookings since the beginning of this year, with visitors of the post-90s and post-00s accounting for nearly half of the total footfall since February as per the Chinese online travel agency Ctrip.

Securing a job and future prosperity in their careers have become priorities amongst these young devout worshippers.

The most sought-after amid the temple fever

Among them, Yonghe Temple, is a special place for these young pilgrims. There is “nothing more efficacious” than the lamasery that once stood as the official residence for Yongzheng (one of the most diligent emperors in Chinese history) before he ascended the throne. The emperor’s dedicated spirit is believed to be a lucky charm for young people who are seeking to progress into the next chapter of their professional lives.

With good tidings from former adorers who received job opportunities after their visits to Yonghe Temple circulating on social media, it has become even more sacred amongst young Chinese and soon emerged as a popular attraction on the internet, propelling the hashtag “Yonghe Temple” to garner more than 150 million views on China’s lifestyle-sharing platform Xiaohongshu, where 72% of its over 200 million monthly active users are post-90s.

The emperor’s dedicated spirit is believed to be a lucky charm for young people who are seeking to advance their professional lives.

Emerging businesses brought out by templegoers

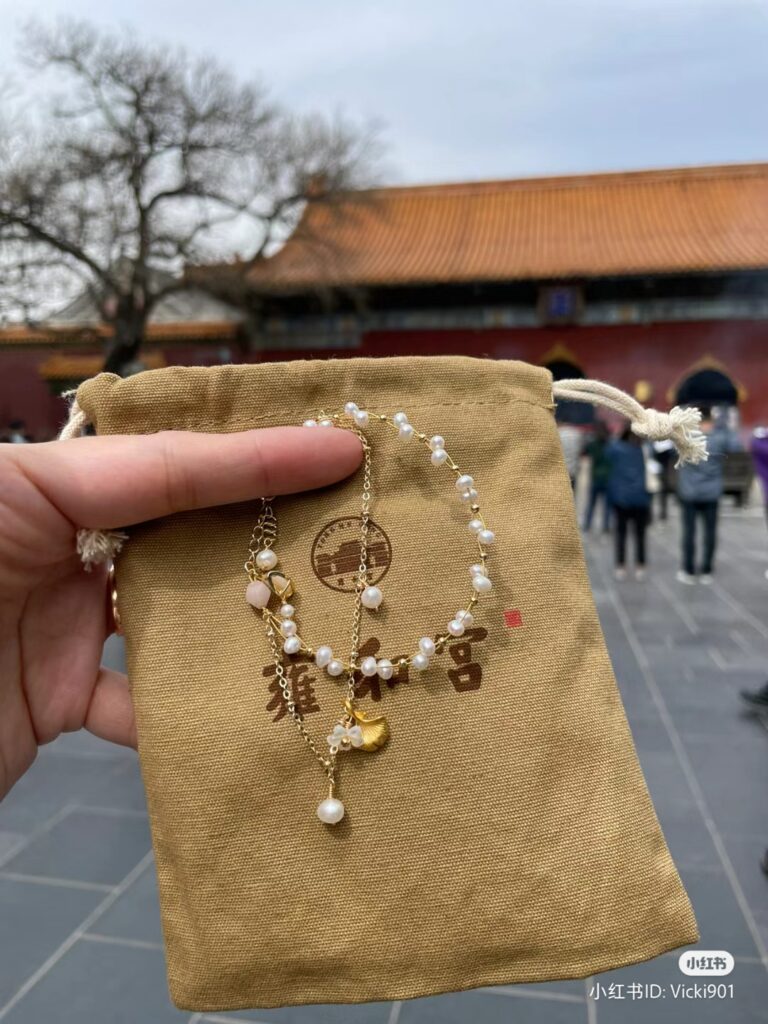

While posts that show queues outside the lamasery in the early hours continue to be commonplace in March, others are sharing their experience including tips on the best pray practices and details of “rules” on burning incense for temple goers who are praying for different reasons, such as passing exams or getting university or job offers. Also trending in the searches are accessories, including Buddha hand chains and necklaces. Normally made of coloured glaze, jade, or wood, these ritualistic items, known amongst worshippers as 法物, are a must-buy after a visit, or in their words 请回 , which means bringing [wishes] back with them, which is deemed a crucial process to make them come true.

This religious enthusiasm not only boosted sales of these “magic items” both offline at the temple and on e-commerce platforms, but also the business of substitute ritual item buyers, or “代请法物”. The Daigou behaviour, where individuals purchase products for those who cannot visit in person while making a profit, has pushed the price of accessories from around one hundred Yuan to more than a thousand, further fuelling the already heated debate around the new obsession of young people.

Online debate over young devotees

The temple fad soon turned into a social media sensation with several relevant hashtags, including “Why has temple tourism become a hit?” and “Media commentary on why young people don’t go to class, don’t have a ‘go-get’ attitude but go pray in a temple”, drawing in over 100 million and 130 million views within 24 hours on 21 March.

Media reporting with a patronising tone, such as the one by The Beijing News, sparked anger amongst the young generations. The publisher indicates that “young people should clearly distinguish between the imaginary and real worlds. If one banks on Gods to realise their hopes, they are going astray.” Some criticism they are being met with is that they are “departing from the general public and have no understanding of the hardships facing the ordinary”, with a reference to a fiercer job market alongside other social challenges involving family pressure, marriage, and parenting.

“We need some spiritual aspects as reassurance and motivation before we go back to fight reality.”

Empathetic media analysis soon arrived, prompting confessions from young netizens, such as one commenting, “To some extent, this is a tragedy of this generation. Uncertain about their future, not looking at science and turning to supernatural beings. Do we like it? No. Because the dark night is too long and there is no light in sight.”

While societal problems such as work pressure, low pay, low marriage rates, and an ever-declining birth rate have become the status quo amongst the young demographics, the sudden temple fever mirrors the deteriorating dilemma in China’s employment market post-pandemic. The country’s urban youth unemployment rate hit a record high of 19.9% in July 2022. While an estimated influx of 11.58 million fresh graduates in 2023 is expected to escalate the battle even more, the economy which was traumatised by the pandemic is yet to provide a solution for these eager job hunters.

“Young people need somewhere to let go of their feelings,” one comment reads, “[the Zen ambiance] it provides a space for us to escape and feel relief,” followed another. “I know it’s not real, but we need some spiritual aspects as reassurance and motivation before we go back to fight reality.”