What with the development of digital currency in China, the last-minute suspension of Ant Group’s record-breaking IPO and new regulations on tech giants and fintech players, there is a lot to be aware of in China’s fintech and banking sphere.

Dao Insights spoke to Yassine Regragui to learn more about recent developments and key trends in China’s fintech environment.

Yassine Regragui is a Fintech & China Expert based in Paris, with over 9 years international working experience, including 6 years in China. Yassine started his career in Shanghai as an entrepreneur. He worked for two Chinese start-ups before building an e-commerce platform with a Chinese partner. Later, he joined the Alibaba Group to accelerate AliExpress.com’s global expansion, and then the Ant Group to launch and lead Alipay’s multilingual app for non-Chinese users. At Deloitte Paris, Yassine has developed the payment and Chinese consulting practice, and led the China Pay offering. Yassine is a certified Fintech expert by Alibaba Business School, and a Fintech & China advisor for banks and global firms. Read more about Yassine here: www.yassineregragui.com

In simple terms, please can you explain what digital currency is and how it works in China?

The CBDC (Central Bank’s Digital Currency) is issued by the Central Bank directly to the end consumer, which differs from the current distribution in which physical currency is dispensed first to banks. Shenzhen authorities recently distributed 50,000 red envelopes (each containing 200RMB) to test the new currency.

Using digital currency in China requires an app but it is innovative in that it will be accessible offline using NFC technology, once all the experiments are finalised and successful. The other key difference from current cashless services, like WeChat or Alipay, is that all merchants will have to accept the digital currency because it is issued by the state.

The CBDC will also increase the inclusivity of finance by opening financial services to the 250 million Chinese people who currently don’t have access.

Digital currency is not exclusive to China: the Bahamas launched the ‘Sand Dollar’, and the ECB are looking at the feasibility of introducing a Digital Euro. Around 80% of the world’s Central Banks are evaluating the idea of implementing a digital currency. This is a response to the rise of private currency, including bitcoin and Facebook’s future launch of Libra. As such, states are looking to digital currency to secure their sovereignty and compete with tech giants which are threatening to become even more powerful than governments.

There have been lots of concerns voiced about the safety and security of digital currency. Considering China’s digital RMB is owned by the government in comparison to bitcoin and other private digital currencies, how financially secure is it?

“In terms of benefits, state-run digital currencies will result in faster payments, less fraud, and a reduction in money laundering and the financing of terrorism.”

Many private digital currencies, like bitcoin, are decentralised cryptocurrencies so there is no central actor. However, China’s digital currency is run by the Central Bank who can guarantee the stability and value of the money. Blockchains can be used to secure it and ultimately the central bank is responsible for issuing it, which provides security to citizens. In terms of benefits, state-run digital currencies will result in faster payments, less fraud, and a reduction in money laundering and the financing of terrorism.

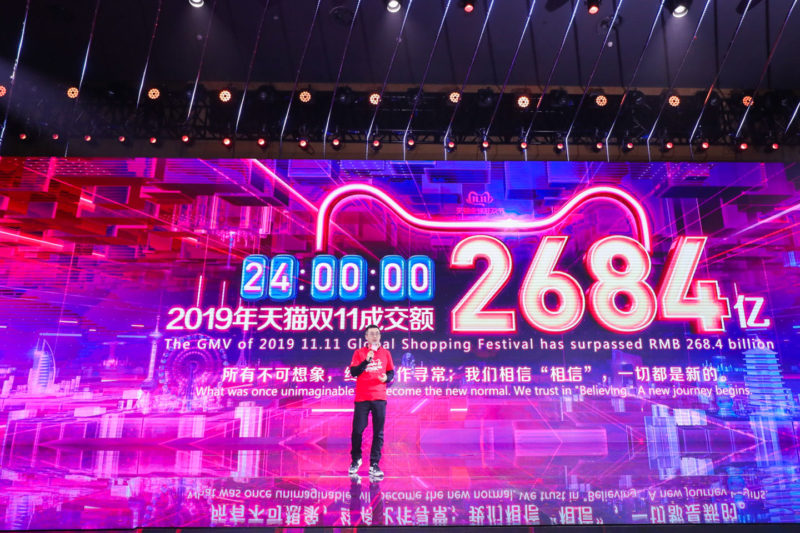

The average value of China’s fintech companies is much greater than those of America, Europe, or the rest of the world. How has China been able to so successfully integrate retail and social activity with financial services (for example, through partnerships with retail platforms e.g. Lufax & Eleme and the integration of WeChat Pay in social app WeChat)?

There are three key reasons. Firstly, user experience is unique in Asia, especially in China, and this has led to the creation of super apps (apps which include a comprehensive range of features within). The notion of a super app was started by Alibaba as their B2B platform transformed into a B2C platform and developed to include a range of other features, including payments with Alipay. However, the launch of a super app was formed through prioritising what the user wants: by analysing users’ data to create new services and improve the existing ones.

Secondly, trust is crucial to the development of China’s super apps. When WeChat launched WeChat Pay in 2015, users seamlessly transitioned to the new service because they already trusted the company, due to using QQ and WeChat.

The third factor is culture: Chinese people love innovation and trying out new features. Super apps are not just limited to WeChat and Alipay – Dianping, Tmall, and JD also have all-encompassing apps. However, this trend, which originated in China, is now spreading to the rest of the world, especially in Southeast Asia with ride-hailing apps like Grab and Go-Jek. Facebook is also considering launching a super app and Google announced that it will introduce ‘Plex’ next year, which will include payments, lifestyle services, loyalty and rewards.

Do you think super apps by Facebook and Google will be successful in the West?

They face big challenges because people in the West prefer separate apps for separate uses, rather than having one app that can be used for everything. It comes down to a difference in culture: people will spend 2-3 hours watching videos on Tmall or Taobao without buying anything because they consider it a form of entertainment and a way to learn about new trends. However, this is unusual in the West.

I think Google’s strategy will work as the company is starting by only including a few features in its Plex super app, like Alipay did at the beginning, and will gradually develop to include more.

Given that Ant Group provides many different payment and finance services to users, how would you define it?

“Techfins are able to offer all kinds of new financial services because their core business is technology.”

Ant Group is defined as a ‘techfin’ because it’s a tech company offering financial services, rather than the other way round. The name change from Ant Financial to Ant Group reflects Ant’s desire to be associated as a techfin. The majority of Ant Group’s microloans revenue comes from technology fees, highlighting that technology is key to the company’s business model.

Techfins are able to offer all kinds of new financial services, including paytech, creditech, insurtech and investech, because their core business is technology, such as AI, blockchain and the cloud.

Can you give a brief summary of the suspension of Ant Group’s IPO – what happened and why.

The main interesting takeaway is that Chinese regulators are drawing the line and no longer want one or two big leaders to dominate the microloans and fintech market. According to new regulations for microloans, microlenders must fund at least 30% of any joint loan with a financial institution, while Ant’s current funding is only around 2% of the credit outstanding.

The regulations will force fintechs to innovate and will result in the development of more fintech actors. China wants to have more big players which can compete globally.

In addition, the new regulations will ensure that banks play a more important role. They will bring a new wave of innovation from traditional banks who have previously been in the shadow of these big fintechs.

Do you think Ant Group will still be able to list on the Hong Kong and Shanghai stock exchanges in 2021? What needs to happen for its IPO to be approved?

“One of [Ant’s] values is ‘embrace change’ 拥抱变化 and the company puts a strong focus on adaptability and never giving up.”

As well as the increase to 30% funding for microloans, there are other regulations that Ant Group will need to abide to, such as a more equal spread of capital funding for microloans throughout China. Therefore, I think it will take a few months to align with these regulations.

However, the IPO is not cancelled, and I believe it will take place in 2021 or 2022 depending on how quickly they can adapt. Investors trust Ant and I know that it is a very resilient company from my experience of working there. One of the values is ‘embrace change’ (拥抱变化) and the company puts a strong focus on adaptability and never giving up.

Fintech giant Lufax, which is an associate of Ping An Group, postponed its plans to IPO in Hong Kong and decided to list in the US instead with a valuation of approximately $30 billion. Why has Lufax chosen to IPO in the US and what are the implications of that decision?

Lufax considered Shanghai and Hong Kong for its IPO but ultimately chose the US because it had the right investors and analysts for microloans. I think this was the right initial listing for the company due to the investor environment in the US and it will probably also decide to list in Hong Kong and Shanghai in the future.

What impact will the new antitrust regulations that were announced on November 10 have on China’s fintech environment? Do you think increased regulation is harming the development of China’s fintech environment?

China’s tech companies have a lot of businesses so the new regulations will probably only affect one or two of them. In relation to Ant Group, microloans will be the main business affected but it only represents 40% of total operations.

Regulations on tech giants are not something new and China was previously lacking in this regard. If China wants to achieve its goal of being a world power in 2049, it needs to put baselines in place. The new rules highlight the ambition of Chinese regulators to have a growing number of tech companies and allow more entrepreneurs to enter the market.

Are China’s tech companies now so large that it is impossible for new entrants to catch up?

Too big to fail is definitely correct in relation to China’s tech giants.

Too big to fail is definitely correct in relation to China’s tech giants. However, there are a lot of new companies, such as ByteDance and JD, which have been able to emerge in the past few years. While it may have been more difficult for them to reach Tencent or Alibaba’s level, these new regulations will encourage new entrepreneurs to raise funds, launch new businesses and compete with existing tech giants.

Although BAT (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent) are big today, they may not necessarily be big tomorrow: a message which is often highlighted by Jack Ma (the founder of Alibaba). Being humble, embracing change and being innovative are traits specific to Chinese companies.

Indeed, the new regulations are not aiming to stop big tech firms, but rather to guide them on the right way to develop globally and to promote more equality in the field.

As more and more Chinese people take loans thanks to Ant and Tencent’s services, new regulations are also necessary to avoid a subprime financial crisis similar to the one in 2008. They are also a response to the growth of online business as there is a risk of separation of online and offline business so the regulations will help to bridge this gap.

What can we expect from China’s fintech market in the 2020s?

I envisage three marked trends: an increase in sovereignty from the state with experiments of the CDBC which will bring new waves of innovation. Secondly, the increase in regulation on fintechs will give banks more room to innovate. Subsequently, banks will not do the same job as before and will transform to compete or be complementary with fintechs. Finally, we will also see the growth of open finance, as more and more companies that are not directly related to finance, launch financial services, as Starbucks and Uber have done. In this way, open finance will allow any company to offer financial services, starting with payments.

If you enjoyed this article and want to contribute a piece to Dao, please get in touch with the team at [email protected]