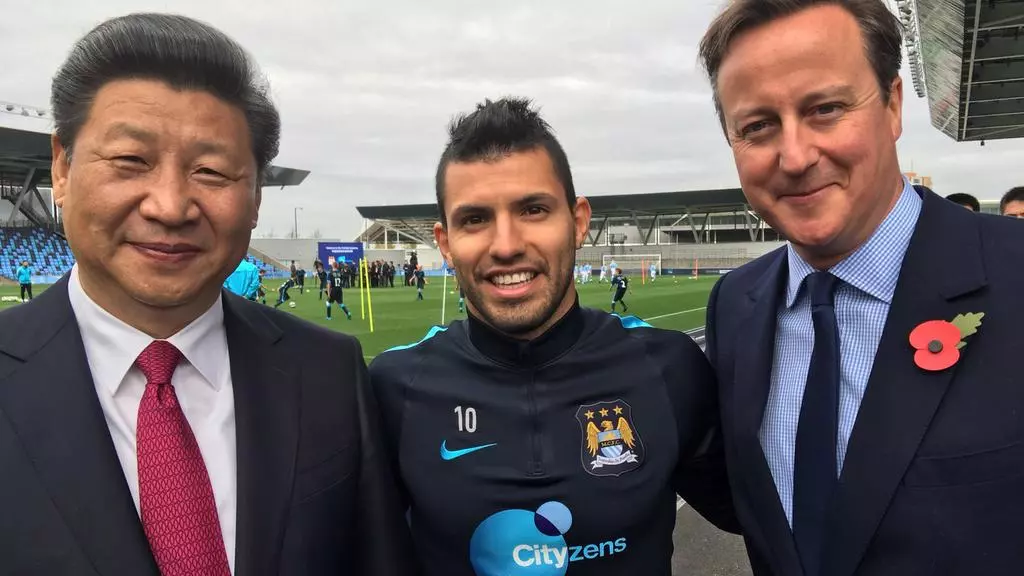

In 2015, during his last visit to the UK, President Xi Jinping, an avid football fan, stated his intention for China to be a ‘World Football Superpower’ by 2050. In doing so, he pledged that there would be 20,000 football training centres and 70,000 pitches across the nation by that point. With those great expectations in mind, there are subsequent questions regarding how this plan has fared and what China has been doing to achieve these goals?

The influx of foreign talent on and off the pitch

According to data from 2018, the Chinese Super League (CSL) was the sixth highest attended professional football league in the world after the Premier League, Bundesliga, La Liga, Serie A, and Liga MX, with an average attendance of 24,107 per game across the season. Moreover, in the same year, 40,000 tickets for the World Cup were purchased by Chinese fans. Given that China did not qualify on this occasion, it seems that there is something else that is drawing fans’ interest towards the game.

If we look at the CSL at this very moment in time, each team within the league has four foreign players in their match day squads. Chinese football currently boasts an array of stars such as Oscar, Hulk and Paulinho to name a few. Lest we forget that it was only twelve months ago that Gareth Bale was on the verge of joining Jiangsu Suning in Nanjing, while Didier Drogba and Nicholas Anelka were gracing China’s stadiums some eight years earlier.

Off the pitch, there has been an increasing number of high-profile managers that have been attracted to the growth of the CSL and have brought spectators with them. Since 1994, when Leeds United’s first division winning manager Howard Wilkinson took over at Shanghai Shenhua, the likes of Chris Coleman, Sven Goran Eriksson, Andre Villas Boas and Fabio Cannavaro have joined the CSL. There has even been an influx of incredibly gifted coaches, physios and technical staff that have left a legacy which will hopefully continue to grow in the future.

It is no coincidence that Ian Walker, who enjoyed a great career in the UK, has nurtured and developed China’s previous two number one goalkeepers, Yan Junling and Wang Dalei, during his tenure at Shanghai Shenhua and Shanghai SIPG. Furthermore, in the treatment room, the latter club is home to the world’s first seven figure physio, Eduardo Santos, who has been regularly visited from stars across the world seeking his help to stay injury free.

At a corporate level, there has also been considerable investment from the world’s largest clubs in building new teams, such as Manchester City with Sichuan Jiuniu, and Barcelona with their academies in the region. The blueprint is clearly there and is proving successful in terms of popularity growth and fan engagement, but how has this impacted the Chinese national team?

The rule of naturalisation – quick win or sustainable long term approach?

Having missed out on every World Cup since 2002, during which they suffered three losses and failed to score a single goal, it is fair to say that being ranked 76th in the world will not provide much encouragement for Xi Jinping’s ongoing plans to be a football superpower.

Clearly there is something deeper rooted across the nation that is holding back its national team from any real achievement whether that be lifestyle, the onus on academia or the standard of grassroots coaching. The naturalisation of foreign-born stars, whose ability surpasses the majority of the current crop within the national team, is currently proving to be a short-term solution.

The multitude of Brazilian born stars plying their trade in the CSL are willing to give up their nationality in favour of sporting the famous red of China. Currently, Elkerson Cardozo (Ai Ke Sen- 埃克森), Fernandinho (Fei Nan Duo – 费南多), Aloísio dos Santos Gonçalves (Lou Guo Fu – 洛国富) and Ricardo Goulart (Gao La Te – 高拉特) have all been integrated into the squad. Elkeson has already shown his goalscoring prowess in Chinese colours.

From Europe, the same is true of the former premier league players for Arsenal and Everton, Nico Yennaris ( Li Ke- 李可) and Tyias Browning ( Jiang Guangtai- 蒋光太), as well as the less renowned John Hou Saeter ( Hou Yongyong – 侯永永). Unlike the aforementioned Brazilian cohort, the European turned Chinese Nationals actually have origins in China.

Whilst it may provide an immediate upheaval in the quality of the national football team, once these players are at retirement age the cycle would have to begin again, and, do so effectively, to be able to maintain the same standards.

Success starts at home

So far, we have looked at how China has outsourced genuine quality both on and off the pitch. However, the simple sporting question remains of whether the best solution would be to start organically from within its borders and at a lower level?

In the last 20 years, there has rarely been a Chinese national who has enjoyed a successful footballing career overseas. There has been the likes of Li Tie, Zheng Zhi and Sun Jihai who were at Everton, Charlton and Manchester City respectively, and even the more high-profile acquisition of Dong Fangzhuo by Manchester United who was labelled as having the “speed and physicality” to crack the Premier League. Needless to say, I imagine the majority of people reading this do not recall these names which gives an indication of how their careers fared in the West.

Nevertheless, fast forward to 2020 and Wu Lei, the CSL’s all-time leading goal scorer, found himself as a favourite in Spain’s Espanyol having scored against their Barcelona rivals in a home derby and gaining the highly coveted number 7 shirt. More recently, there have also been the potential transfers of Zhang Linpeng and Yan Junling to Chelsea and Granada which failed to materialise, as well as the unsuccessful stints of Wei Shihao and Zhang Yuning in Portugal and the UK.

Whilst their spells abroad may not have been memorable, they have come back to China and excelled. European clubs have chosen to pursue Wei once again as he continues to impress with champion team, Guangzhou Evergrande. The recently published ‘Next Generation 2020’ of footballers by The Guardian also highlighted the potential of Shanghai SIPG’s Jia Boyan who at 16 years of age has shown immense ability domestically.

Is the goal of winning a World Cup by 2050 realistic?

One thing that is clear to me having studied and experienced the game first hand in China is that the potential is there. I believe that with the right education, coaching and development from a grassroots level, China could see a real progression in players.

By maintaining the correct lifestyle and mindset as well as being exposed to some of the best mentoring available China could indeed climb up the ranks. With the right application there are no doubts in my mind that players from the CSL will thrive on a global stage which will hopefully translate into more achievements for the national team. Whether this happens or not remains to be seen but one thing for sure is that the journey, as with all things in China, will be fascinating to watch.

Learn more about football in China:

- Case study: FC Barcelona Springs Into Colour for Chinese New Year

- Deal with Tencent Sports means Premier League returns to China

- Check out our podcast below:

If you enjoyed this article and want to contribute a piece to Dao, please get in touch with the team at [email protected]