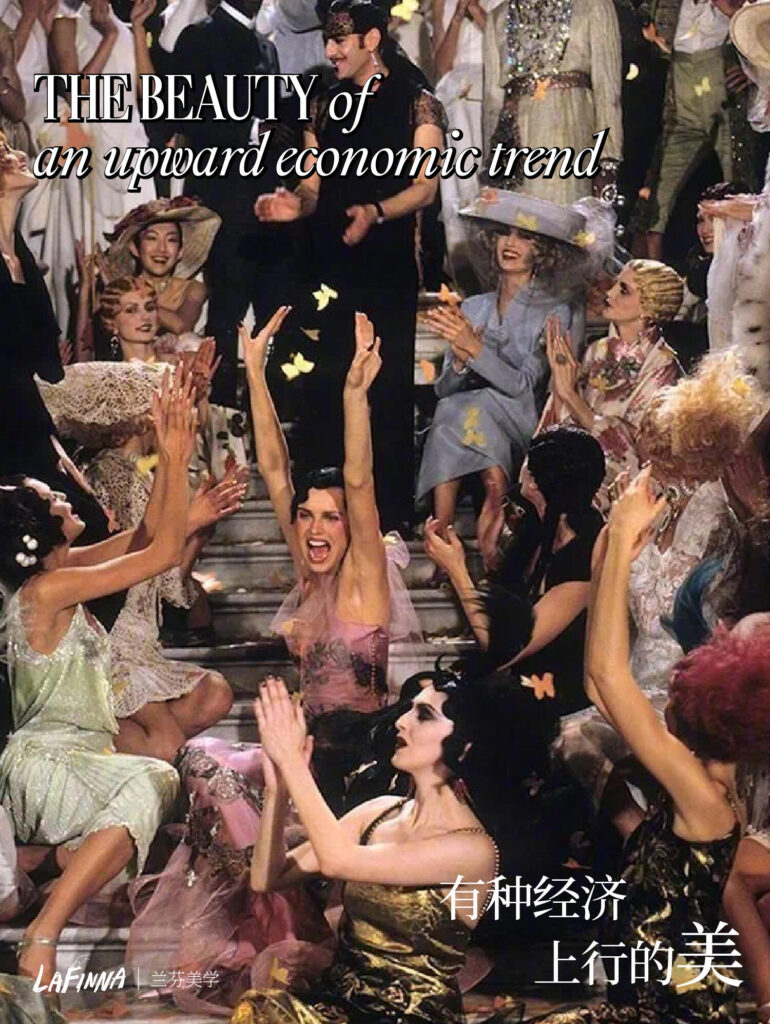

At the end of August, while Western fashion magazines lamented a summer without trends, there was a definitive one in China. Only, it is less of a fashion trend (though it is one) and more of a social sentiment: the craving for the “beauty of economic upswing” (经济上行期的美).

Some pundits see it as an extension of the earlier sub-cultural trend “Chinese dreamcore”, which blends an early digital, psychedelic aesthetic with childhood nostalgia for the 1990s and 2000s, often involving dreams of time travel. But as the name suggests, it is more of a grown-up sentiment among young professionals towards that era. After all, those who grew up in those years weren’t old enough to understand what the economic upswing meant until after the fact.

Rose-tinted spectacles

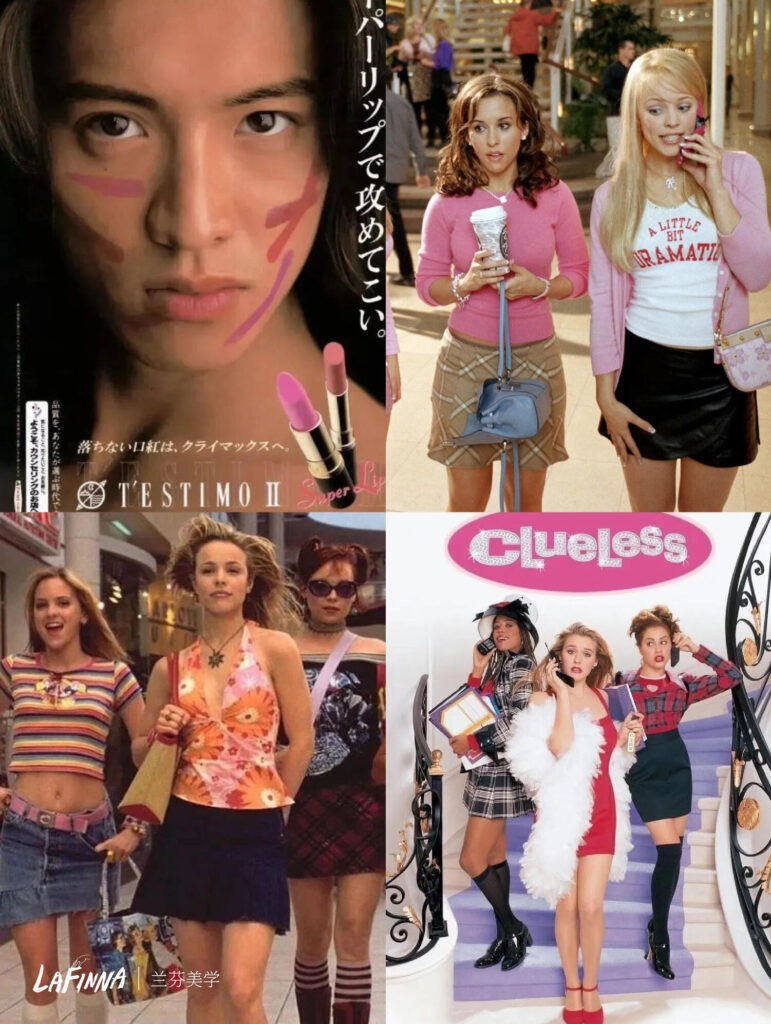

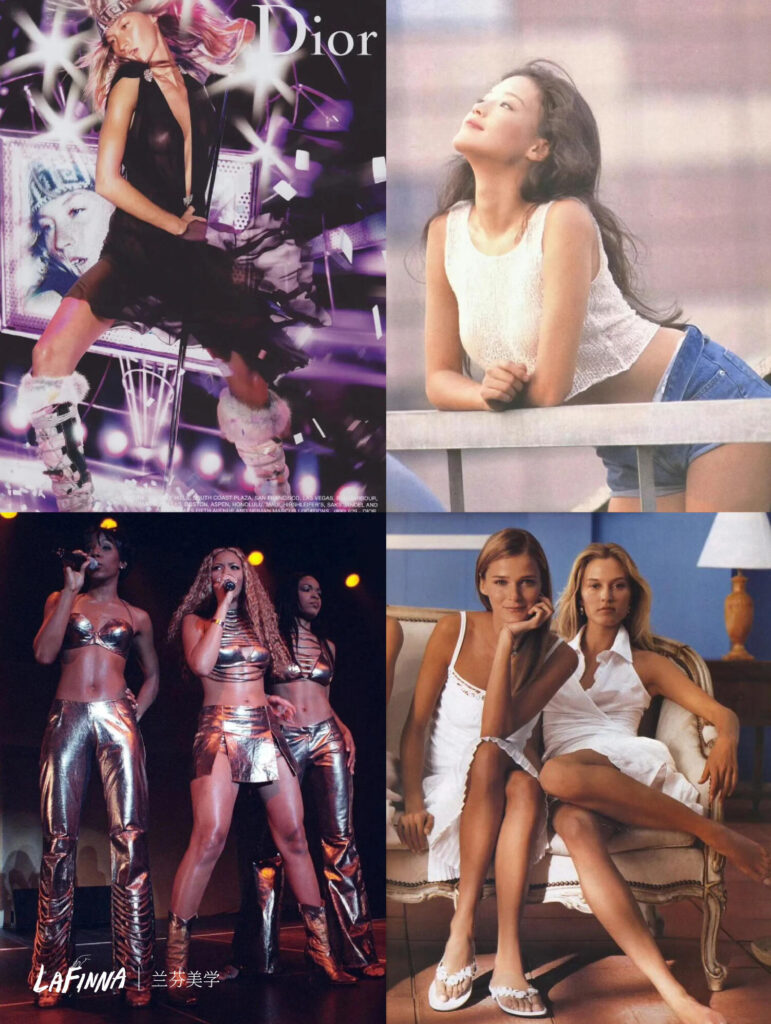

Since earlier this year, especially in early summer, a viral trend on social platforms such as Rednote and WeChat introduced the phrase to many. The trend itself centres on how great “your mum’s wardrobe” was 20 years ago. The phrase “beauty of economic upswing” began circulating, usually to describe outfits or old photos, often street snaps. It partially coincides with the Y2K resurgence and broader nostalgia trends of recent years, but with a distinctly Chinese background.

The “beauty” of the era has been elevated to capture the spirit of a hopeful society

Quickly, the concept of the phrase expanded, since beauty is rarely used to describe just visual attraction. The “beauty” of the era has been elevated to capture the spirit of a hopeful society, one that had joined the World Trade Organisation, won the bid for the Olympic Games, and was finding its place on the world stage at the start of the new century. Some suggest it was a time when people firmly believed that tomorrow would be better than today, and that hard work would pay off.

The golden age fallacy

Commentators quickly pointed out that China is not the only one looking back on its most recent heyday. Japan is also revisiting the 80s and early 90s “bubble economy” era. From the revival of the 1980s “city pop” genre of R&B music to the growing interest in “Shōwa nostalgia”, young people in Japan are reflecting on a time when the country was looking ahead during an economic boom. Similarly, Hollywood often looks back on the United States’ various “golden ages” throughout the post-war period. For today’s generation, the 90s and Y2K era is likely the last “golden age” remembered, despite the 911 tragedy that shifted the grand narrative away from endless progress.

For the same reason, the 1990s and Y2K fashion have been featured heavily in today’s mainstream designs, providing the backdrop for the Chinese version to thrive. From “you wake up one afternoon in 2006” (which garnered over 8 million views on Rednote) to waves of content showcasing late 1990s and 2000s toys and stationery, the post-80s and post-90s generations are revisiting the culture they grew up with.

These are the good old days

Hashtags such as “retro” (古早, lit. means ancient), “2000s”, “millennium”, and “Chinese dreamcore” have gone viral on platforms such as Douyin, with hundreds of millions of views. Influencers not only try on their mother’s wardrobe but also recreate iconic looks from the 1980s to the 2000s, inspired by pop culture.

Chinese Y2K nostalgia is born out of economic uncertainty and young people’s lack of optimism

As with its global counterpart, Chinese Y2K nostalgia is born out of economic uncertainty and young people’s lack of optimism. Much of the “beauty of economic upswing” comes from the bold fashion, use of colour and designs that contrast with today’s “quiet luxury” or minimal aesthetic. For this reason, many young people dress in the Y2K style to give themselves motivation and confidence, just like the young people walking the streets of Beijing in 2008.

For this very reason, I argue that the trend is not a reactive or escapist sentiment. A report from Goofish shows that young people today are still fighting for a better future by taking on second jobs. On the platform, 9.45 million people are working second jobs, with 40.8% from the post-00 generation. Goofish also sees the “emotional value” of certain hobbies and interests as “therapeutic”, such as pet-keeping, which was a 300 billion RMB (41,94 billion USD) business in 2024 and designer toys, a 60 billion RMB (8.39 billion USD) business; together, they have been healing over 1 billion people in China. Each generation has its own way of dealing with the world. As long as young people today are still working towards a better tomorrow, who says that when they look back in 10 or 15 years, these won’t be the good old days they miss?

Need to boost your China strategy? Dao Pro delivers bespoke insights on marketing, innovation, and digital trends, direct from Chinese sources. Find out more from our Dao Strategy Team here.