Village cafés, or small-town coffee shops, have been a closely monitored phenomenon in China. There are two types of coffee shops discussed here. One is mostly concentrated in lower-tier cities and larger “county seat” towns. These are sometimes chains and franchises that have expanded to catch the tea and coffee boom in China, such as Luckin and Cotti. The other, mostly in smaller towns or even villages, are independent coffee shops. Some local chains also exist.

Data shows that there are over 44,000 rural coffee shops and cafés in China. The provinces with the most “village coffee shops” are Yunnan, Guangdong, Anhui, Henan and Zhejiang. The top two provinces, Yunnan and Guangdong, have 11,915 and 7,786 rural coffee places, respectively. This is thought to be because they are the two major origins of coffee beans in China.

Business or Pleasure

For many small towns and rural areas, coffee shops are an extension of B&Bs and “cultural tourism”

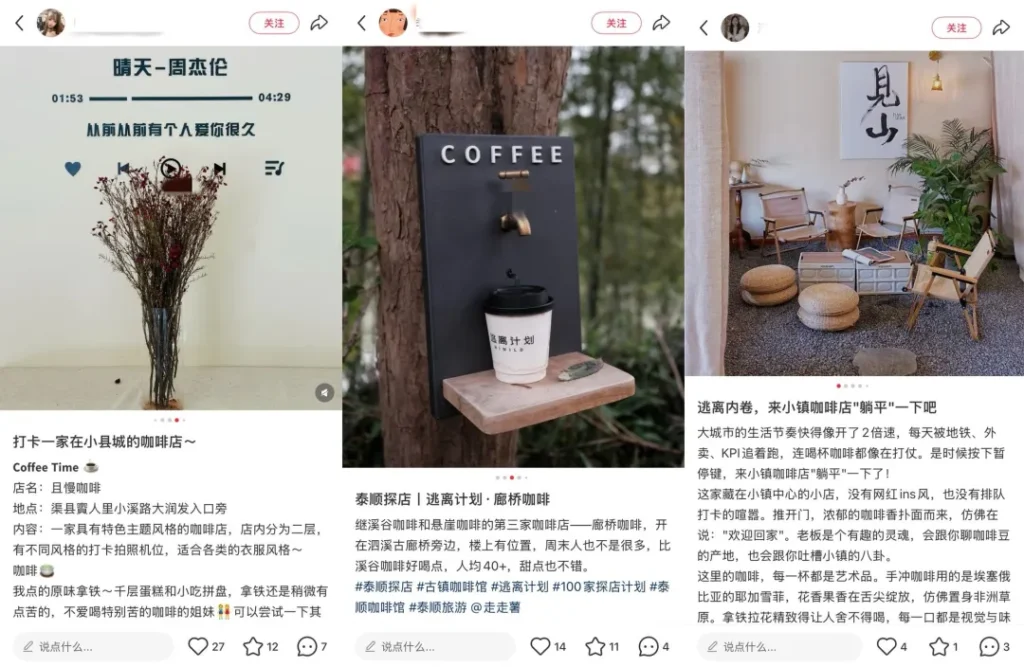

Many of the coffee consumers in these rural regions are, in fact, travellers. For many small towns and rural areas, coffee shops are an extension of B&Bs and “cultural tourism”. For travellers, this type of tour is a “lighter” version of camping, living in rural houses built during the Qing era and washing down local cuisine with a nice cup of coffee.

This business model, however, relied heavily on in-province travel and was especially popular during the pandemic. But with travel restrictions lifted, many travellers have shifted back to longer-distance travel, both domestically and internationally. As the trend of “lighter” lifestyle also reached tourism, a steady niche of visitors still prefer small towns close to the cities where they work or within the same province.

Local governments also see this as an opportunity to boost both travel and help small businesses

Local governments also see this as an opportunity to boost both travel and help small businesses, with Zhongshan, Guangdong, providing rent subsidies and Zhejiang helping entrepreneurs with taxes. However, this has also led to a sense of saturation, with competition from large chains, new entrepreneurs, and even hotel lobbies pushing the market into a state of “involution” (内卷, fruitless competition).

After the initial wave of “check-in” (打卡), caused mostly by the novelty of having coffee shops in small towns, many of these rural and small-town coffee places are now evolving into concept cafés or themed coffee shops, providing immersive local experiences of the culture, be it a traditional or rustic lifestyle or, should the region permit, ethnic minority cultures. Providing hot food, either pizza to go with the Western theme of coffee or local delicacies, is another sphere of competition.

Digital Nomadland

Earlier this year, the rent increase in Dali, Yunnan, a favourite of digital nomads seeking the pastoral “poetry and elsewhere” (诗和远方), caused many to reconsider where they roam. In light of new developments in small towns, many decided to return to their hometowns to continue their digital nomad work out of local coffee shops.

In fact, during Chinese New Year earlier this year, a trend became something of a hit meme: urban young professionals, “Lily” and “Kevin”, returned home only to become “Cuihua” (翠花) and “Dazhu” (大柱) in their hometowns during the festival. Coffee shops, be they large chains like Luckin Coffee or independent and craft coffee places, offered them both a continuation of their urban lifestyle and a space for socialising.

Now, many have relocated back to their hometowns for their remote jobs. Coffee shops, in this case, play a similar role to what they do in larger cities, but with fewer distractions as they are away from busy shopping areas. Many people, both visitors and residents, seek “songchigan” (松弛感, sense of looseness, chillax) in small-town life, and find that these coffee shops embody almost everything they’re looking for.

However, the business of “village coffee” is not all fun and games. Not only has the aforementioned saturation led to fierce competition, but it has also caused homogeneity, as not every coffee shop can afford to find its own unique selling proposition. For example, a checked tablecloth, a bamboo wicker basket and an “Instagram-style” presentation are what many call the “big three” elements of a rustic coffee place. With cafés having similar aesthetics, some are pointing out that they are starting to look just like the ones in the cities, with the same interior design. Items like rice-flavoured coffee are also being copied and pasted onto nearly every menu.

At the same time, the cost of opening a coffee shop in a small town or in a village can still be high, especially if you need to restore an old building to get the rustic feel you want. With water and power being essential, renovating a “village café” can set you back anywhere between 400,000 RMB (55,912.76 USD) and 1 million RMB (139,781.90 USD). However, with 2,053 new coffee shop openings across the country, albeit mostly chains, in June alone, the coffee boom is far from over. The question is whether “village coffee” can continue to exist in its current form.